A few days ago, I received a DM in my Instagram inbox from someone I didn’t know. I could see the beginning of the message: “Did you see this…” Typically, these types of messengers are sharing videos they think I might find inspiring (e.g., innovative veganization of Korean dishes, really heartwarming stories about Korean immigrants, etc.) or they’re giving me a heads up on something that might concern me (e.g., someone using my content without credit, an account pretending to be me, etc.). I therefore tapped on the message, hoping it would be a “nothing burger.”

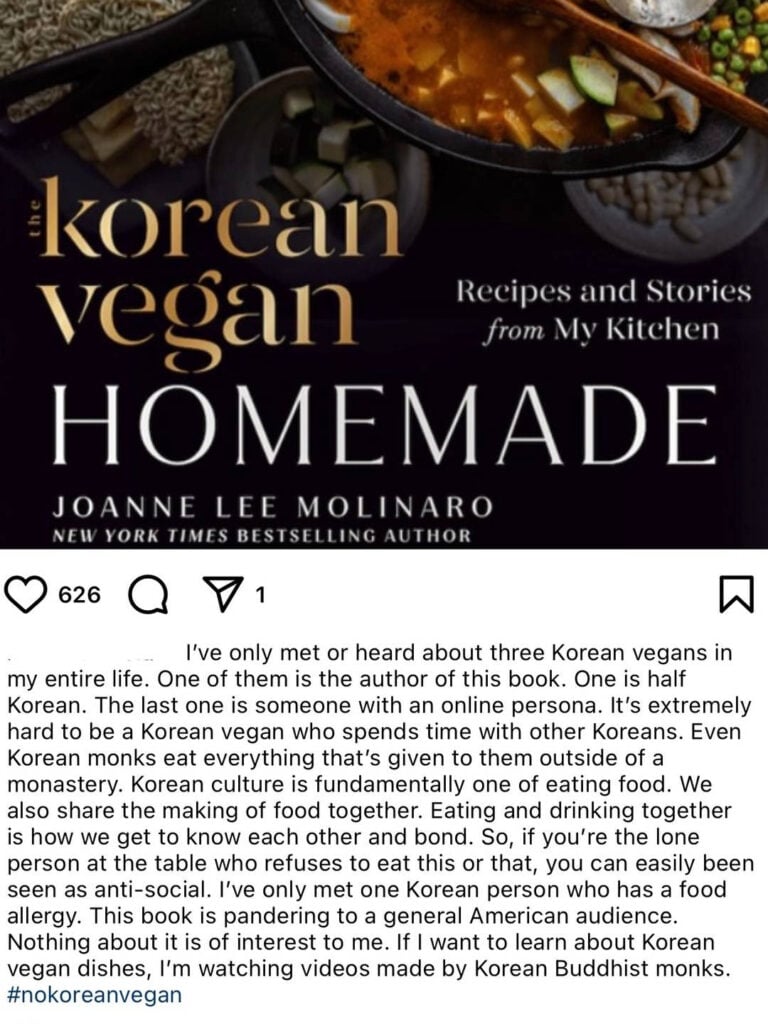

The woman DM’ing was a fan and wanted to alert me to another Korean American content creator who had recently posted something about my forthcoming book, The Korean Vegan HOMEMADE. In fact, the post was a photo of the cover with a long-ish caption. There was, however, nothing in the DM that suggested whether it was a negative or positive post. Should I be worried? or would I be moved? Intrigued, I tapped on the shared post and scrolled down to the caption.

It begins with “I’ve only met or heard about three Korean vegans in my entire life. One of them is the author of this book.”

So far, nothin’ bad.

“It’s extremely hard to be a Korean vegan who spends time with other Koreans.”

Ok… given what I’ve written myself about visiting South Korea, I can’t disagree.

The content creator then goes onto describe how important “eating food” is to Korean culture: “Korean culture is fundamentally one of eating food. We also share the making of food together. Eating and drinking together is how we get to know each other and bond.” Again, I can’t disagree, though, I would add that the practice of eating, sharing, and cooking food is “fundamental” to just about every culture on the planet since, as humans, we require food to survive as a species!

The Instagrammer than posits that those who refuse a certain food due to their ethical choices (i.e., because you’re vegan) risk being rude and thus unable to participate in the “fundamental” rites of bonding she referenced in the earlier sentence, to wit: “if you’re the lone person at the table who refuses to eat this or that, you can easily be seen as anti-social.”

The red flags began to emerge as I made my way to the bottom of her meandering paragraph of observations, which she ends with the following:

“This book is pandering to a general American audience. Nothing about it is of interest to me. If I want to learn about Korean vegan dishes, I’m watching videos made by Korean Buddhist monks. #nokoreanvegan”

Look, I know what some of you are saying to yourselves (though you may not ever hit “send” on the email containing said thoughts): “What’s the big deal? So she doesn’t like your book. Not everyone will. Grow a thicker skin, will ya?”

Here’s why I don’t think it’s just a matter of one person not liking my book (because there will be a lot more than one person who won’t like my book!).

First of all, this woman has over 12,000 followers on Instagram. Many of these followers include people I know in the Korean American community–people who also have substantial reach over their communities. People I considered to be my friends. That level of subscription equates to exponential influence–influence she chose to use against me and my book, a book she hasn’t read yet (unless she committed a literal crime). The post went out to her thousands of followers and garnered (the last I checked before blocking her) over 600 “likes.”

Second, the creator positions herself as an expert on Korean culture. She’s a bit older than I am (in her mid-50s) and was born and raised in Korea (unlike myself). While her statements regarding the challenge associated with practicing veganism in South Korea are true, and there are potential social implications for refusing certain dishes because of your ethical stance on consuming animal products (as if these don’t exist elsewhere…), the conclusion she sets forth, that there is “#nokoreanvegan,” is, in a word, outdated:

As of 2021, there were approximately 2.5 million people in Korea following a vegan diet. (Id.) This represents a staggering 1,556% increase in the past 13 years. Put another way, “[t]he number of vegans has increased tenfold from 2008 to 2018, and has shown a growth of around 67 percent in the three years after that.” (Id.) K-pop idols and k-drama stars are embracing the vegan diet. Indeed, it was the director of the Oscar award winning movie, Parasite, Bong Joon-ho, who helmed the film Okja–a heart crushing film that reveals with unflinching temerity the horrors of Big-Ag and is responsible for making many people remove animal products from their diet. The fact that my first book, The Korean Vegan Cookbook, was translated into Korean and is now being sold in bookstores all throughout South Korea is, itself, an extraordinary testament (if I can pat myself on the back here) to just how explosively the vegan movement has taken hold of the Korean zeitgeist.

So, in addition to choosing to use her influence against me and my work, she does so with the employment of misinformation.

Third, the creator pits individual ethics against traditional norms, heavily implying that one obviously outweighs the other and that they can never happily coexist. In so doing, she also implies that traditions are, by their nature, infallible and should never be questioned. This is a frequent but pernicious conflation that occurs in diaspora: you miss your native culture so your native culture is perfect. It is an exploitation of the immigrant’s longing for community and cultural connection for the reinforcement of unchecked nationalism (the bad kind) and the existing infrastructures of power. She gets to be the gatekeeper of “what is Korean,” and she derives a sliver of power from that role, while, of course, channeling the rest of it to the power dynamic that has had a stranglehold on Korea for millennia.

I’ll pause here to say I love Korea. I hope to live there while I work on my next book. Nothing would bring me greater joy than growing intimately familiar with the nation that shaped my parents and my grandparents. I am also proud of Korea. While I am by no means a political scholar, I can see how much the people of Korea value their franchisement (77% voter turnout) and the protection of their relatively nascent democracy. When I compare their recent and decisive rebuttal to the idiotic deployment of martial law to our own nation’s response to January 6, I am filled with deep admiration and respect for the Korean people.

But I am not a Koreaboo. I am not a Korea apologist.

The wealth gap in Korea is a problem that no one but the obscenely wealthy (i.e., the chaebols) will deny. Korea remains decidedly behind the United States or other western nations when it comes to dismantling homophobia, anti-Blackness, and rampant Islamophobia. And of course, there is the age-old problem of misogyny.

Of all nations of high income economies, South Korea ranks dead last when it comes to the gender pay gap, with women earning approximately 31% less than their male peers. Women are woefully underrepresented in positions of leadership or high-wage earning jobs and many large (prestigious) institutions have had to defend against disturbing allegations of gender discrimination and recruitment practices designed to favor men. In short, there are far fewer seats at the table for Korean women than there are for Korean men.

And that brings us right back around to the Korean American woman who took time out of her day, space on her Instagram feed, good will from her not insubstantial community, to dedicate an entire unsolicited and wholly unprovoked post against another Korean American woman.

There’s this really compelling modern parable about a very wealthy landlord who throws a massive banquet at his beautiful mansion. He invites his wealthy landlord peers, other individuals of industry, and all of his tenant farmers (who are decidedly not wealthy). All of the landlord’s guests arrive at the address, excited to partake in a sumptuous meal full of interesting people. But it soon becomes apparent that not all guests are equal. Some are welcomed at the great, mahogany double doors at the front of the landlord’s home, while others are funneled through a shabby side entrance, out of view. While those greeted at the front are shown promptly to a humongous banquet table crammed with enough gourmet food and wine to feed a small city, those who come via the side door are led to a crowded, dimly lit hall in the basement where the fare is composed of a watery soup, stale bread, and barely edible fruitcake.

Both sets of guests sit down to enjoy their meals–the wealthy landlords at a golden table, the tenants on random stools and picnic benches. The host begins to make his rounds, greeting his guests, high-fiving his real estate bros, asking his servers to bring out more caskets of wine, the “good stuff” for the men of industry getting drunk inside his home. Then, he heads downstairs to the basement, where he greets his tenants with a hardly manufactured exuberance: “Well, I hope you all are enjoying your free food!” He starts walking around the crowded room with mixed expressions of artificial concern when he says things like, “How’s Jessie? He’s around 5 years old now?” or “Yeah, I know, the tariffs are just killin’ me too!” or “I wish there was something I could do to lower our grocery bills.”

Eventually, he comes to a small, hastily erected card table where two of his tenants are seated. One of them is an older woman, a loyal tenant farmer, one who has worked hard and without complaint for decades. Seated next to her is a younger woman, a relatively new recruit to the landlord’s farming enterprise. He puts a hand on each woman’s shoulder before saying, “Thank you both for the work you do. I appreciate you.” He picks his hands up and makes as if he’s going to exit the room, but just before he does, he bends over and whispers the following into his loyal tenant’s ear:

“Better watch out,” he warns, nodding towards the young woman seated next to her. “She’s going to steal your fruitcake.”

I’m sure the above needs no explanation. Also, by now, you will hopefully understand why I’ve chosen to keep this person anonymous. Who she is isn’t relevant. Suffice it to say, I can hazard a guess as to why this person felt compelled to publicly denigrate my work. Because I’ve been there. I’ve been the jealous, toxic Korean American woman who let her envy get the better of her. When I see other Korean American women thriving in Hollywood, when I see other Korean American female content creators going viral on TikTok, when I see other Korean American businesswomen building household brands–I get jealous. And I ask myself why isn’t that ME?

Because there’s some ingrained part of me that knows that for every seat at the table–even a shitty table full of shitty food–that gets occupied by her means one less seat being saved for me.

And it is powerfully tempting to train my resentment on the one right next to me, instead of the dude upstairs grandstanding with his peers.

Luckily, though, I am a smart person! LOLOLOL. I’m also a nice person, hehehe. I not only recognized my ugly feelings for what they were and never ever ever in a million years acted out on them, I also figured out why I had them. My parents, who grew up in poverty and fear, gifted me with the afore-detailed scarcity mentality, which, of course, was reinforced by systemic racism and misogyny throughout my life and career. Having arrived at this breakthrough, I concluded that the answer could not be running over my fellow Korean American women, but running with them. In fact, making sure to cheer them on, offering them some water out of my water bottle, or even handing over a couple ibuprofens when the race gets tough. Because the only solution to being relegated to the basement is to ensure that as many of us as possible cross the finish line, where there is more than enough to feed all of us if there are enough of us to wrest the excess from those who would keep it from us.

I’ve heard from a lot of women who’ve confessed to harboring similar feelings, which is why I’m sharing my own experience here at the risk of being maligned by all of you (I mean, not really, because you all are really nice, compassionate people). I’ve been both the subject and object of jealousy and neither is a good situation. I’ve heard less from men who’ve felt this way (Anthony, for example, has never felt anything remotely similar), but I don’t doubt that some form of this may exist with men, too. We may not want to own up to the former, because it seems petty, ugly, and unkind. But it is impossible to eradicate these things if we don’t confront them and we can’t confront them if we don’t talk about them with honesty.

I’m always curious to hear your thoughts (when conveyed politely!). Drop them below. Oh, and, as always, thanks for letting me share, safely.

Parting Thoughts

When my first book came out in 2021, my publisher scheduled a few days of a truncated book tour in Los Angeles so that I could sign books and do a couple of events. Quarantine had been lifted (I was lucky in that my book came out during the short lull between Delta and Omicron) and folks came out to stand in line, purchase extra copies, and chat with me about what my stories meant to them. At a smaller signing at my favorite vegan cafe (Joi Cafe in Westlake Village), a long line curled out from under the eaves of the small strip mall.

Among them was a Korean American woman who drove in all the way from Burbank with her two boys. She told me she was proud of me and even as I write this sentence, the tears are welling. This was four years ago and it still means so freaking much to me, precisely because I know how easily that pride could have been resentment; because of how lonely and hurt I felt when other Korean Americans lambasted me for being “whitewashed” and fake. The next day, she came by to the independent bookstore where I was signing their stock. She apologized for being “stalkerish,” but she wanted me to sign more books for her friends and she brought me some vegan snacks, to keep me energized throughout the tour.

I don’t have any sisters. I’m the eldest female of my generation here in the United States. I have older female cousins in Korea, but given how infrequently I get to see them, I don’t often get to use the word “Unni”–the word for “older sister” in Korean. “Unni” denotes so much–too much for me to include in these Parting Thoughts. As I gave this woman a hug and thanked her over and over again, “Unni” echoed in my head and lingered long after the sight of her disappeared.

Wishing you all the best,

Wishing you all the best,

-Joanne

English (US) ·

English (US) ·